An examination of data from the Attorney-General’s Department tells us which firms have failed to meet targets, writes Jacqueline (Jaci) Burns.

Recently, I wrote that pro bono targets should be mandatory for LSMUL winners. By way of reminder, LSMUL is shorthand for the Australian government’s legal services panel. Following a competitive tender, 62 law firms were recently appointed to the Commonwealth’s five-year, “billion-dollar” panel.

It’s 2019. We should not still be arguing the case for good corporate citizenship. For law firms, pro bono work is a central pillar of any corporate responsibility program.

The aspirational target is not a recent invention. The target of 35 hours (pro bono per lawyer per year) should have ceased being an aspiration long ago.

For the Australian government’s panel law firms, achievement of the target should be non-negotiable.

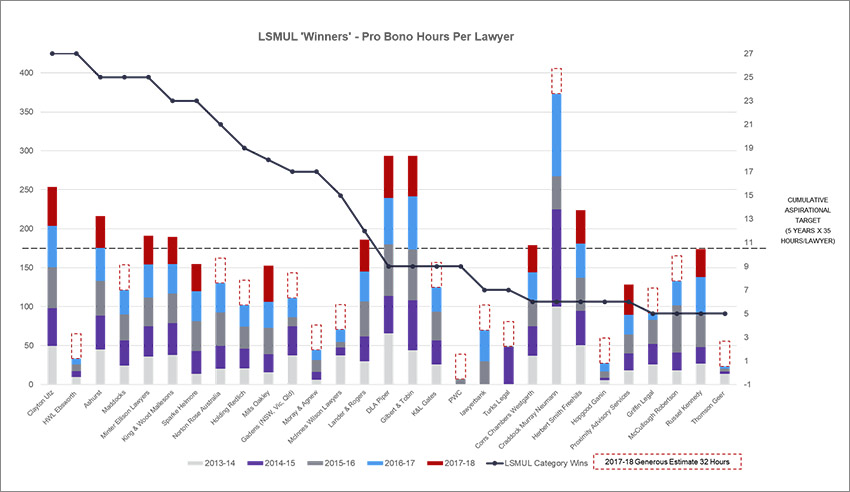

It is unreasonable to judge a firm’s pro bono commitment based on what it has done in a single year. I’ve therefore analysed the pro bono hours reported by the LSMUL “big winners” (firms that were appointed to five or more areas of law) for the past five years.

Cumulatively, “committed” firms should have recorded at least 175 pro bono hours per lawyer – the equivalent of 35 hours multiplied by five years.

Annoyingly, in 2017-18, the Attorney-General only published the hours recorded by the firms that met or exceeded the aspirational target. So, for example, we know for sure that Lander & Rogers reported 41 pro bono hours per lawyer for that year; Gilbert & Tobin, 52.

We don’t know precisely how many pro bono hours were recorded by those firms that did not meet the target. We only know that Maddocks, Moray & Agnew and many, many other LSMUL “big winners” failed to meet the target in 2017-18.

Because I’m interested in assessing long-term commitment to pro bono work, for the sake of the analysis I’ve generously estimated each “failing” firm recorded 32 hours per lawyer (not the desired 35 hours) in 2017-18.

What does the data tell us?

Observations

1. Craddock Murray Neumann is far and away the firm most committed to pro bono work.

2. It’s easy to identify which firms have the best run pro bono programs. Firms such as Gilbert & Tobin, DLA Piper, Clayton Utz and Herbert Smith all report consistently high pro bono hours – well above aspirational target. This indicates pro bono work is a fixture, not a fad.

3. It’s apparent that some firms provide pro bono services occasionally. Turks Legal, for example, recorded an impressive 48 hours per lawyer in 2014-15, but has recorded almost nothing since. My assumption is Turks ran a pro bono transaction or piece of litigation in 2015.

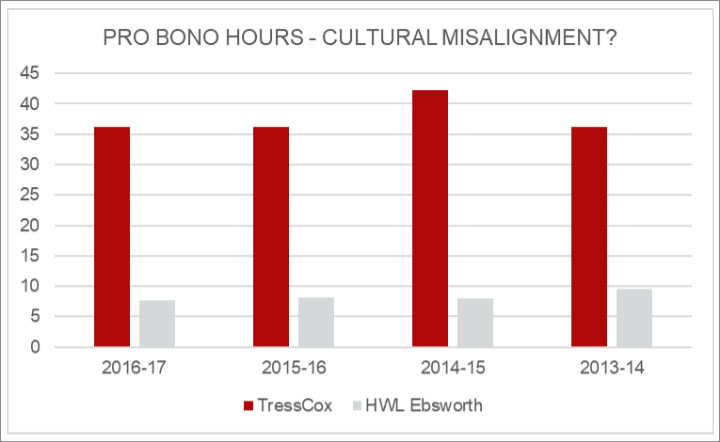

4. As for HWL Ebsworth…in addition to exposing this firm’s poor pro bono record, this analysis reveals a possible cultural misalignment between HWL Ebsworth and TressCox. Prior to those two firms “joining forces” in 2018, TressCox was deeply committed to pro bono work. Let’s hope the former partners of TressCox can affect positive change at their new firm.

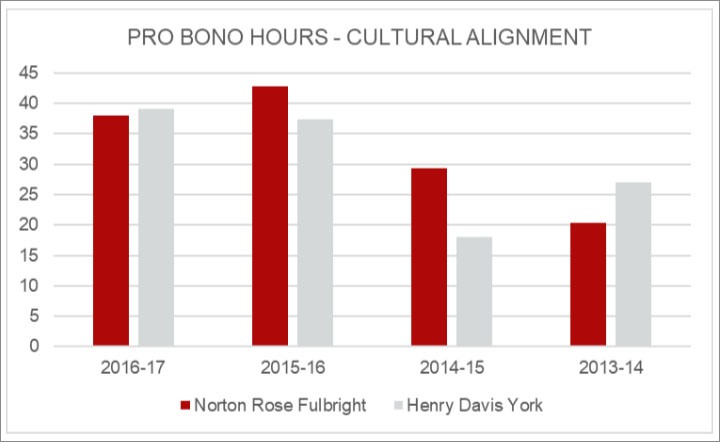

In contrast, consider how well aligned were Norton Rose and Henry Davis York. Prior to merging, both firms shared a similarly strong commitment to pro bono work. As an integrated practice, that commitment has held steady.

Jacqueline (Jaci) Burns is a chief marketing officer at Market Expertise.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: "In my previous article I stated that 46 (75 per cent) of the new LSMUL firms were yet to achieve the pro bono Aspirational Target. That was incorrect. 46 firms did not achieve the Target in 2017-18. Three firms - McCullough Robertson, K&L Gates and Norton Rose Fulbright – have, in fact, achieved the Target in previous years."

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Russell Kennedy's hours per lawyer for 16/17 were eight hours, rather than 48.3 hours. The Office of Legal Services Coordination in the AG’s Department have acknowledged an error in the legal services expenditure report for FY16/17.